The collapse of the Qing Dynasty is perhaps one of the most important events in Chinese history, marking the end of more than two millenniums of imperial rule. The success of the Xinhai Revolution in 1912 resulted in the formation of the Republic of China, as well as forcing the abdication of the six year old reigning emperor, Aisin-Gioro Puyi (爱新觉罗 溥仪). Despite losing status as emperor, Puyi was still able to live in relative luxury in the Forbidden City, and later Tianjin with his family for nearly two decades, where he found himself influenced by several warlords and the Japanese. Wishing to reascend to the throne, Puyi found himself increasingly reliant on the Japanese for assistance, and made his intentions known to them. The outbreak of the Mukden Incident on September 18th of 1931 provided Puyi and the Japanese with a unique opportunity to fulfill both of their goals. Under the guise of retaliating against an attack on their railway tracks, the Japanese attacked Chinese garrison forces and were able to take over most major towns and cities by February of 1932. Meanwhile, Puyi was invited to Mukden (then called Fengtian, modern-day Shenyang), where the Japanese promised he would head a new state formed in Manchuria (Manchoukuo). Guaranteed that he would be made emperor if he agreed to go to Mukden, however upon his arrival, Puyi learned that the new state would be a republic.

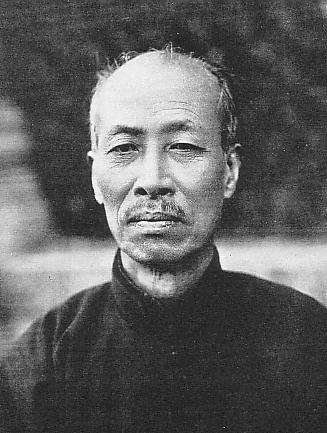

Seething with anger from this betrayal, Puyi demanded that the Japanese keep their promise and allow him to reascend to the throne, threatening to return to Tianjin and then live in exile abroad. Soon, he would send his subordinates Zheng Xiaoxu (郑孝胥) and Luo Zhengyu (罗振玉) to meet with General Seishirō Itagaki (板垣 征四郎) with the intention of discussing Puyi’s wish for immediate restoration to the throne. Accordingly, he prepared gifts for Itagaki as well as a comprehensive list of eight reasons why he believed that the new state in Manchuria should be a monarchy rather than a republic, and why he needed must reascend to the throne immediately. Puyi called Chinese writer / poet Chen Zengshou (陈曾寿) to help him write down his thoughts, and accepted four of Chen’s additions to the list. (The final four reasons of the twelve were written by Chen). Alternatively, this list can be seen as interpreted as Puyi’s ultimatum to the Japanese.

The following Chinese text is taken directly from the original Chinese publication of Puyi’s memoirs, while the English text was taken from Paul Kramer’s English translation with slight modifications.

- 尊重东亚五千年道德,不得不正统系。/ The right system is essential if we are to follow the moral code of East Asia which dates back five millennia.

- 实行王道,首重伦常纲纪,不得不正统系。/ The right system is essential to the carrying out of the Kingly Way and moral principles.

- 统驭国家,必使人民信仰钦敬,不得不正统系。/ To rule the state one must have the trust and respect of the people, and for this the right system is essential.

- 中日两国为兄弟之邦,欲图共存共荣,必须尊崇固有之道德,使两国人民有同等之精神,此不得不正统系。/ China and Japan are fraternal countries, and for their joint survival and welfare they must respect the time-honored morality and ensure that both peoples have an identical spirit. For this the right system is essential.

- 中国遭民主制度之害已二十余年,除少数自私自利者,其多数人民厌恶共和,思念本朝,故不得不正统系。/ China has suffered from the disasters of democracy for over two decades, and, apart from a selfish minority, the great majority of the people loathe the Republic and long for the Qing Dynasty. For this reason the right system is essential.

- 满蒙人民素来保存旧习惯,欲使之信服,不得不正统系。/ The Manchu and Mongol peoples have always preserved their ancient customs, and the right system is essential if we are to win their allegiance.

- 共和制度日炽,加以失业人民日众,与日本帝国实有莫大之隐忧;若中国得以恢复帝制,于两国人民思想上。精神上保存至大,此不得不正统系。/ The Republican system is very widespread while the numbers of the unemployed daily increase. This constitutes a most serious threat to the Japanese Empire, but if the imperial order is revived in China, this will do a great deal to preserve the intellectual and spiritual qualities of the peoples of our two countries. For this reason the right system is essential.

- 大清在中华有二百余年之历史,(入关前)在满洲有一百余年之历史,从人民之习惯,安人民之心理,治地方之安靖,存东方之精神,行王政之复古,巩固贵国我国之皇统,不得不正统系。/ The Great Qing has a history of over two hundred years in China and of over a century in Manchuria before that. To observe the way of life of the people, calm their minds, maintain the peace of all parts of the country, preserve the Oriental spirit, carry out the revival of the Kingly government and consolidate the imperial order in our two countries, it is essential to have the right system.

- 贵国之兴隆,在明治大帝之王政。观其训谕群工,莫不推扬道德,教以忠义。科学兼采欧美,道德必本诸孔孟,保存东方固有之精神,挽回孺染欧风之弊习,故能万众人心亲上师长,保护国家,如手足之捍头目。此予之所敬佩者。为起步明治大帝,不能不正统系。/ The rise of Japan dates from the Kingly rule of Emperor Meiji. His edicts to his ministers all propagate morality and give instruction in loyalty and righteousness. While science was learned from Europe and America, morality was based on Confucius and Mencius. Since the ancient spirit of the Orient was preserved and the people were saved from the contagion of disgusting European practices, they love and esteem their elders, and protect their country as readily as one’s hand protects one’s head. That is why I respect him. The right system is essential if we are to follow in the steps of the great Emperor Meiji.

- 蒙古诸王公仍袭旧号,若行共和制度,欲取消其以前爵号,则因失望而人心涣散,更无由统制之,故不能不正统系。/ The Mongol princes continue to use their old titles, and if they are abolished under a republic they will be disappointed and disaffected, and there will be no way of ruling them. For this reason the right system is essential.

- 贵国扶助东三省,为三千万人民谋幸福,至可感佩。惟子之志愿,不仅在东三省之三千万人民,实欲以东三省为张本,而振兴全国之人心,以救民于水火,推至于东亚共存共荣,即贵国之九千万人民皆有息息相关之理,两国政体不得歧异。为振兴两国国势起见,不得不正统系。/ Japan deserves our deepest admiration for the way in which she has assisted the Three Eastern Provinces [the Northeast] and taken thought for the welfare of their thirty million people. My wish is that we should not restrict ourselves to thirty million people but should take the Three Eastern Provinces as a base from which to arouse the whole nation and save the people from the disasters that have befallen them. This would lead to the common survival and prosperity of East Asia, a matter which closely involves all of the ninety million people of Japan. There should therefore be no divergence between the political systems of our two countries. To bring about the prosperity of both countries is indispensable.

- 予自辛亥逊政,退处民间,今已二十年矣,毫无为一己尊崇之心,专以救民为宗旨。只要有人出而任天下之重,以正道挽回劫运,子虽为一平民,亦所欣愿。若必欲予承之,本个人之意见,非正名定分,实有用人行政之权,成一独立国家,不能挽回二十年来之弊政。否则有名无实,诸多牵制,毫无补救于民,如水益深,如火益热,徒负初心,更滋罪戾,此万万不敢承认者也。倘专为一己尊荣起见,则二十年来杜门削迹,一旦加之以土地人民,无论为总统,为王位,其所得已多,尚有何不足之念。实以所主张者纯为人民,纯为国家,纯为中日两国,纯为东亚大局起见,无一毫私利存乎其间,故不能不正统系。/ Since I retired from office in 1911, I have lived among the people for twenty years. I have had no thought for my personal glory and have been guided only by a wish to save the people. If someone else would undertake the responsibility for the country and bring disasters to an end with the True Way, I would be happy to remain a commoner. If I am forced to assume this burden, it is my personal opinion that without the correct title and real power to appoint officials and administer the country, I will be unable to bring twenty years of misgovernment to an end. If I am ruler only in name and am hedged in by restrictions, I will be of no help to the people and will only make their plight worse. This would not be my original intention, and would increase my guilt, and I absolutely refuse to bear the responsibility for this. If I were only concerned about my personal glory, I would be only too pleased to be given the land and the people after two decades of living in obscurity. What would I care about whether I become president or monarch? It is purely for the sake of the people, of the state, of our two countries of China and Japan, and of East Asia as a whole, and not because of the slightest self-interest, that I maintain that the right system is indispensable.

Prior to the meeting, Puyi told Zheng and Luo to stand by his views and to present the list of demands to Itagaki. However, Zheng went against Puyi’s wishes and did not present the list. On the contrary, he agreed with the Japanese perspective that the new state should indeed be a republic. After returning, Zheng tried in vain to convince Puyi to accept the position of “Chief Executive” (执政). In Zheng’s perspective, the only way that Puyi would be able to reascend to the throne was to rely on the Japanese. As such, it would be wise to not upset the Japanese. However, Puyi refused to budge. Soon however, Itagaki would request to meet Puyi in-person to discuss state matters. After nearly three hours of Puyi arguing his case, a calm and collected Itagaki informed Puyi that they would continue the conversation tomorrow. The following day however, Itagaki issued a definitive statement to Puyi, stating that the terms of the Japanese will not be altered, and any further protesting or defiance on Puyi’s behalf will be treated as a sign of hostility and be dealt with accordingly. (“军部的要求再不能有所更改。如果不接受,只能被看做是敌对态度,只有用对待敌人的手段做答复。这是军部最后的话!”) With this threat, Puyi had no choice but to give in to the Japanese. He reluctantly accepted the position of Chief Executive soon after, and was given the ruling title of Datong (大同). However, the following year, Puyi would officially be recognized as the emperor of Manchoukuo, and kept that title until 1945 when Manchoukuo was overrun by Soviet forces. Nonetheless, the initial struggle for restoration saw Puyi becoming desperate enough to issue an ultimatum. Through the list of reasons he created, one could see that Puyi was staunchly against the idea of a republic, citing cultural and traditional reasons why it would fail. In addition, Puyi praised Japan several times within his list, seemingly to keep on good terms with the Japanese and win their favor. Whether or not he truly meant what he wrote however, we will never know.