When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out on July 7th of 1937, the Republic of China Air Force (ROCAF) was in no condition to face the Japanese head on. With an ineffective industry, the majority of aircraft in service were purchased from foreign nations. In addition, much of the combat aircraft able to be serviced were of rather old design, or simply just lacking in numbers to make an effective fighting force. Nonetheless, the outbreak of war would prevent any sort of industrial overhaul and in fact furthered the reliance of foreign nations to maintain China’s fighting strength. On June 8th, just a month prior to the outbreak of war, the American Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company shipped a single H-75H Hawk (s/n 12327) fighter to the Republic of China to promote their aircraft. After arriving, the H-75H made demonstration flights in August to Chinese officials in Nanjing by Curtiss pilot Peter Brewster. Impressed by the flight characteristics, the demonstrator H-75H was purchased by the Chinese along with thirty H-75Q Hawks. Many more variants of the Hawk would also be purchased and shipped within the next few months, initially having desirable qualities over their Japanese counterparts and proving their worth in combat.

Zhu Jiaren (朱家仁), the director of the 1st AFAMF (Air Force Aircraft Manufacturing Factory / 第一飛機製造廠) recognized that the development of Japanese aircraft far outpaced that of China’s. The introduction of the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter in 1940 was by all means an unpleasant surprise to the ROCAF, demonstrating the need for more modern fighters to be serviced against the Japanese. As such, Zhu proposed the design of a fighter aircraft which would be produced by the 1st AFAMF. The design was christened as the XP-0 (Experimental Pursuit 0, 研驅零式), and after studying the design of the Curtiss H-75 it was decided that the XP-0 would borrow both design features and parts from it. Furthermore, the XP-0 would also use a new type of laminated wood material developed by the Aeronautical Research Institute (航空研究院), which was in development for two years. The control surfaces and spars of the XP-0 was to be from metal, whilst the aircraft wings would be constructed using wood and covered with the aforementioned laminated wood. Further details of the XP-0’s construction is unknown, as no records or documents are known to exist on the aircraft. Unfortunately, despite decades of research by Chinese and Taiwanese historians even with archival access, only few details remain about the XP-0 in general. Nonetheless, the XP-0’s design was completed at an unspecified time in 1942. Construction of a prototype appeared to have been delayed due to the evacuation of the 1st AFAMF from Kunming, Yunan to Guiyang, Guizhou to avoid Japanese aerial threat. Nonetheless, a single prototype was completed in 1943 and was declared fit for flight by the Aeronautical Research Institute.

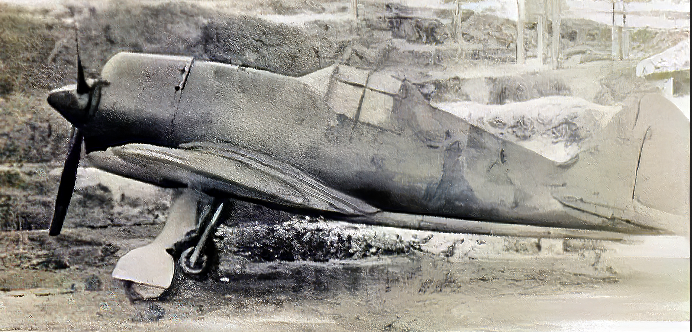

The exact date for the XP-0’s maiden is unknown, but the flight was to take place at the Yangling (楊林) airfield near Kunming. The pilot chosen to perform the flight was Lieutenant Wang Zhongxiao (王中校), a veteran pilot with prior experience flying the H-75. The maiden flight revealed that the XP-0 was a relatively stable plane with no real major flaws other than a slightly higher landing speed than the H-75. Testing would resume for a week, until Wang crashed the XP-0 prototype due to a botched landing. The extended left gear of the XP-0 impacted the ground too quickly and hard, thus destabilizing the plane and causing a tumble. Only the cockpit section remained intact while the rest of the plane fell apart. Despite this, Wang emerged from the cockpit unharmed. The exact reason for the prototype’s crash is unknown, but it could be attributed to pilot error or due to the plane’s relatively fast landing speed. Nonetheless, Wang was able to provide feedback to the design team. Based on the feedback and many other reconsideration, the XP-0 appeared to received several noticeable changes in design as shown by photographs. The initial XP-0 design greatly resembled the H-75, but the second design would appear to have more originality. Two more redesigned examples would be constructed in 1944. Further test flights determined that the XP-0 was comparable to that of purchased American aircraft (likely compared to the H-75). Two more examples would be constructed in 1945 and five more in 1946. Due to the Japanese surrender which concluded the eight years of war, there was no longer a need to continue building aircraft when a steady stream of American lend-lease aircraft was readily available. Unfortunately, the details of the XP-0’s service (if it was serviced at all) is virtually unknown.

With nine examples built after the prototype, it is plausible that the XP-0 was at least used in some capacity. It may have served as a second-line fighter or an advanced fighter trainer, but front-line service seems unlikely as by 1944 the H-75 design (and presumably the XP-0) was already far too obsolete to compete with modern Japanese aircraft. Unfortunately, the remainder of the XP-0’s history remains unknown. They could have been destroyed to prevent capture by Communist Chinese forces during the continuation of the Chinese Civil War, crated and stored in caves, buried or simply scrapped. Thus, the largely undocumented XP-0 can be considered one of China’s attempts during the Second Sino-Japanese War to design and produce their own fighter to compete with the Japanese. Unfortunately, it appears that the design was completed too late to make a difference. Despite this, nine examples were still produced from 1944 to 1946 suggesting that the design was still feasible enough to serve a purpose. If that is the case, the purpose if there is one at all, is unknown. No XP-0 is thought to have survived past the Chinese Civil War.

Though being one of the more well known indigenous fighter designs from the Republic of China, there are still many misconceptions and questionable claims about the XP-0. For one, many Western sources claim that the XP-0’s armament would have consisted of four wing mounted Danish Madsen 20mm cannons as well as being able to carry a torpedo. Meanwhile, the majority of Chinese sources agree the armament would have consisted of an American Browning AN/M2 12.7mm (.50 cal) machine gun and a Browning AN/M2 7.62mm (.30 cal) machine gun. This setup seems far more plausible and likely than the Madsen arrangement considering the large amount of American weaponry made available from lend-lease. In addition, photographic evidence does not show any protruding barrels, but this doesn’t definitely prove that it wasn’t armed with Madsens. As for the torpedo claim, it is highly unlikely that the Chinese would design a torpedo fighter considering that the Japanese controlled most of the coastline and the Republic of Chinese Navy was far too obsolete to compete with Japanese warships in the open seas. In addition, no Chinese or Taiwanese sources make mention of this claim. Hence, this can be considered a baseless rumor. In addition, the same sources refer to the XP-0 as the “Chu X-PO”. The designation does not conform with the designation system adopted by the Nationalist Chinese (which was based on the USAAC/AF designation system) and can definitely be dismissed as an error.

Such a cool airplane. I’m glad that this area of history is finally getting more publicity.

Very interesting, I hope to see you cover other obscure Chinese equipment in the future.

Great documentation on one of the most interest parts of the war of resistance – amazing quality pictures too!

Much appreciated! 🙂

Thank you for shedding more light on this not well known Chinese fighter.

I been studding Chinese aviation from the early time of the kites until 1949 and doing my own color profiles on known aircraft when details are available. Chinese language is a BIG problem for me, I use French, Spanish and English. I did most of my research at the Paris Air Museum and the San Diego Museum.

Keep on posting. I don’t use social media.

JP

Thanks for your encouragement, Baraton.

I have many other articles planned but due to commitments to university and work, I’ll be posting at a much slower pace. Please check back from time to time.

Best regards,

Leo