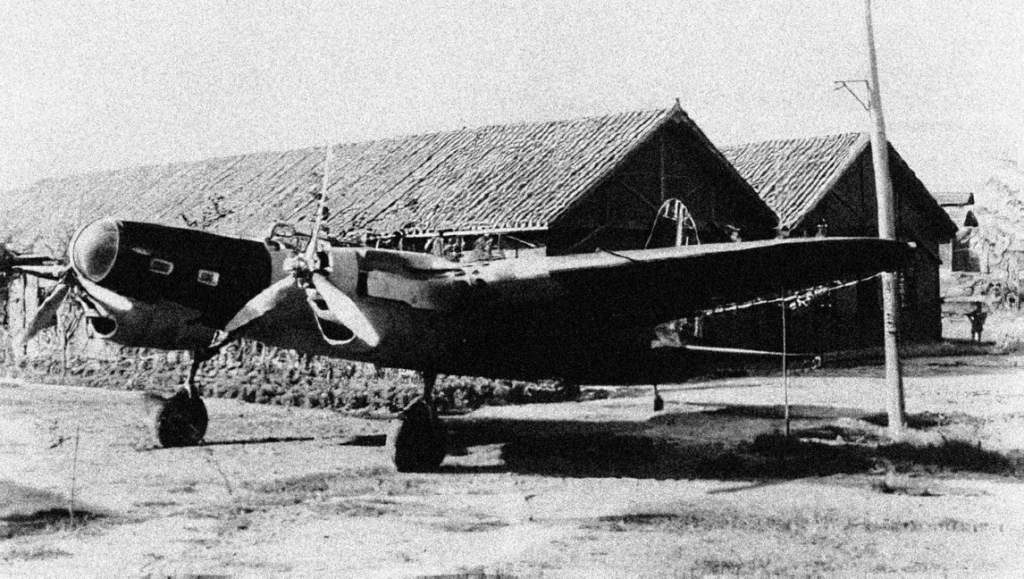

The outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War on July 7th of 1937 saw the Chinese woefully unprepared to face the better armed and trained Japanese. The Chinese Air Force at the time had numerous types but few examples of aircraft in service purchased from foreign nations, creating a logistical nightmare as well as failing to standardize their equipment. Nonetheless, the outbreak of the war provided the Soviet Union with an opportunity to weaken Japan militarily. Signing the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression pact on August 21st, the Soviet Union and the Republic of China reaffirmed ties and created circumstances in which the Soviet Union would be able to provide the Republic of China with military aid. Under “Operation Zet”, the Soviet Union secretly transferred Nationalist Chinese forces large amounts of equipment including small arms, aircraft, tanks, advisors and other essential supplies. Among the many aircraft types transferred were 288 examples of the Tupolev SB (both M-100A and M-103 engine variants). The Tupolev SB was the most numerically available bomber aircraft in the Chinese Air Force, carrying out a considerably large portion of China’s bombing raids in the initial years of the war and indubitably contributing to China’s efforts in their air war against the Japanese. In addition, the Soviet Volunteer Group in China also made good use of the Tupolev SB, having experienced Soviet pilots training Chinese pilots and flying the aircraft on sorties. With the Tupolev SB having proven itself, it would later form the basis of one of China’s only bomber projects of the war, the XB-3.

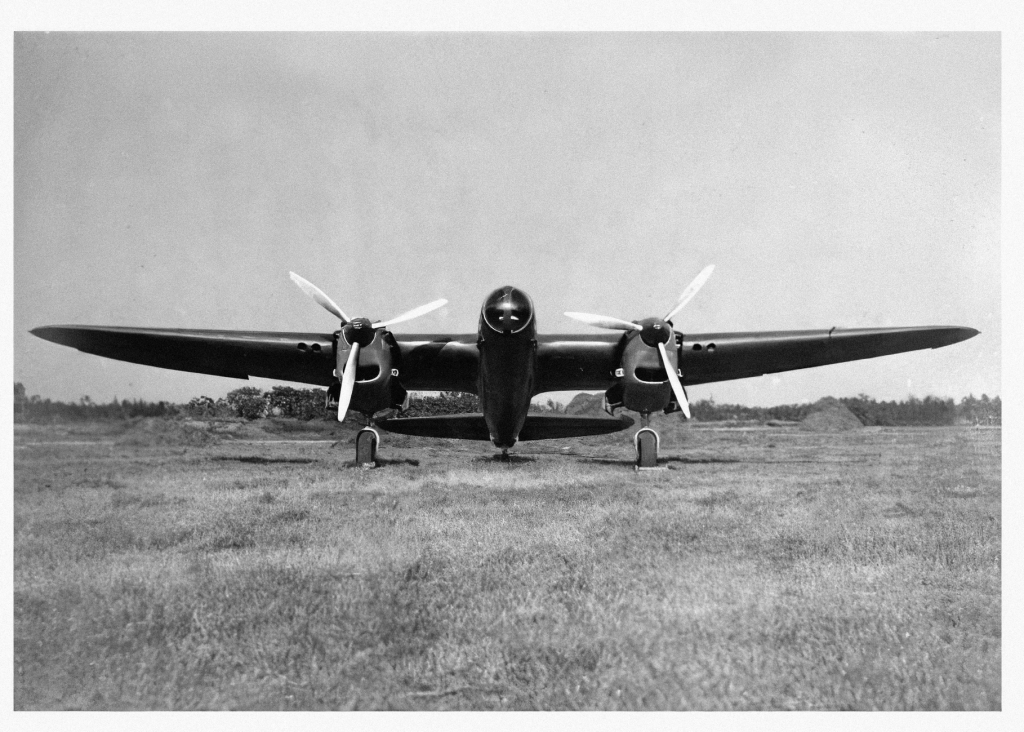

By Minguo 31 (1942), the aircraft industries of the Republic of China had already undertaken numerous indigenous aircraft design projects. Though mainly focused on the development of fighter aircraft, there were also projects to provide the Air Force with transport and trainer aircraft. However, there seemed to lack any real initiative to design a bomber aircraft. To mitigate the increasing losses of bomber aircraft caused by newer and more competitive Japanese fighters and to reduce the reliance on foreign imports, a decision was made by the 3rd AFAMF to design a medium bomber aircraft. The project began in September of 1942 and the two head designers assigned to this project were Zhen Baoyuan (鄭葆源), the factory chief, and Tang Xunyi (唐勳貽), the chief designer of the Design Bureau. Collaborating with the Aeronautical Research Institute (航空研究院), it was soon decided that the new bomber would be developed as a twin-engine medium bomber. An obvious candidate for design research was the Tupolev SB, which proved itself as a capable bomber during the initial years of the war. Following the evaluation and study of the Tupolev SB’s ergonomics and construction, a design would soon be completed by the team. Designated as the “XB-3 Medium Bomber” (研轟三式中型轟炸機), the finished design bore a vague resemblance to the Tupolev SB but with several distinct features which would set it apart from each other. However, the influence that the Tupolev SB had on the XB-3 is undeniably visible.

Objectively speaking, the XB-3 was not necessarily an exact copy of the Tupolev SB but rather an indigenous development and adaptation of the original Soviet design. Though sharing many common parts (such as engines, propellers, landing gears and instrument panel gauges) taken either from part stockpiles or written-off bombers, the XB-3’s fuselage and material composition were of indigenous Chinese design. Unlike the Tupolev SB which had an all-metal construction, the XB-3 had a mixed construction due to a lack of resources. The wing spars and fuselage structure of the XB-3 were made of wood, while the aircraft skin was constructed out of a special bamboo-based aircraft skin layer developed by the Aeronautical Research Institute. The engines of the XB-3 were Soviet-made Klimov M-103 V-12 liquid-cooled piston engines, identical to the ones on some of the Tupolev SB China operated. It was suggested by some modern publications that the Ilyushin DB-3 bomber’s design also played a role in the development of the XB-3. Armament-wise, no reliable source exists which is able to state a definitive armament setup, but a commonly given figure regarding defensive armament is three 7.62mm / .30 cal machine guns. In the author’s opinion, these are most likely Soviet ShKAS machine guns. As is the case for nearly all of China’s indigenous wartime projects, reliable dimension and performance statistics are nearly nonexistent. This is corroborated by the fact that all reliable contemporary and modern literature abstain from giving any aircraft dimensions.

With constant Japanese-conducted air raids near the Eastern region of Chengdu around Shahebao (沙河堡) where the 3rd AFAMF’s production facilities were located, only one example of the XB-3 was able to be manufactured in October of 1943. The XB-3 prototype was disassembled and transported to the Taipingsi Airfield (太平寺机场) in January of 1944 to Chengdu, where it was reassembled and prepared for test flights. The XB-3’s maiden flight was conducted by Huang Rongxiang (黃榮想) and it sought to test the aircraft’s ability to taxi and perform take-offs. It was successfully completed without any major issues. The second flight test was undertaken by Tang Xunyi (唐勳貽), and the purpose was to perform low-level fights around the airfield to test maneuverability. Once again, the test flight successfully concluded without major issues. However, on the third flight, the XB-3 crashed after thirty minutes of flight time. Upon landing, it is commonly said that the pilot (whose name is unknown in this case) was unable to extend both landing gears and made a disastrous landing with only one gear extended. The gear broke and forced the aircraft into a spin, destroying the wing section and causing the airframe to slide dozens of meters. The aircraft did not set on fire, but the pilot was heavily injured after this ordeal. The wreck of the XB-3 was recovered the following day and dumped outside the airport. After this unfortunate incident, the design team decided to cease all work on the XB-3. When taking in mind that the XB-3 was based upon a pre-war design, it is evident that the aircraft would have been highly outdated by 1944 if it were to see front-line service. The few amounts of Tupolev SB bombers still in service with the Chinese were generally relegated to second-line missions, or not flown at all. The American Lend-Lease Act had already provided the Republic of China with sufficient amounts of North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, which essentially replaced the Tupolev SB in the role of a front-line bomber. It would make no logical sense for the XB-3 to see production at this point. Thus, the crash of the XB-3 prototype drew an end to the project.

Curiously enough, certain modern publications from the Republic of China (Taiwan) state that two XB-3 prototypes were actually produced, and that the development of the XB-3 continued until 1946, after the crash of the first prototype. The second XB-3 prototype was allegedly completed in October of 1944. Two more prototypes entered production, but were never to be completed. The third prototype was stated to have been 41% complete in March of 1945, and after an evaluation conducted by members of the Aviation Research Institute in April, it was decided to produce another prototype. By December of 1945, the fourth prototype was 37% complete. These publications argue that due to the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Second World War in general, the Air Force no longer required these types of aircraft to be produced. The project was officially cancelled in 1946 when staff members of the XB-3’s design team were called to relocate to Formosa (Taiwan) and occupy a former Japanese airfield. This narrative contradicts the vast majority of other literature published about the XB-3, and even contradicts an official publication of the Republic of China’s Executive Yuan. In the 1947 book “我國怎樣製造飛機” (How Our Country Produced Aircraft) published by the Information / News Bureau of the governmental Executive Yuan (行政院新聞局印行), it states that only one XB-3 was produced. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there is no truth to this alternate narrative. The aircraft project could have just been “officially” cancelled, and the design team may have unofficially continued with the design. Nonetheless with the unfortunate lack of reliable, consistent and easily accessible information regarding the XB-3, it will be impossible to obtain a comprehensive history of this obscure bomber project of the wartime aviation industry of the Republic of China.